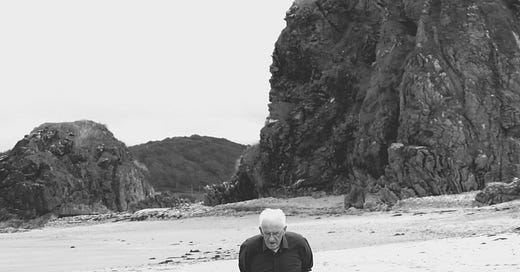

Silent grief: Parental estrangement at life’s end

Understanding the Hidden Grief of Estranged Parents

I recently read Kylie Agllias’ paper, No Longer on Speaking Terms: The Losses Associated With Family Estrangement at the End of Life. It explores the profound, often unspoken grief experienced by elderly parents estranged from their children, focusing on practical recommendations for clinicians working with elderly individuals facing such rifts. While I have often approached this topic from the perspective of the estranged child, focusing solely on one viewpoint overlooks the complexities of estrangement. To truly understand this painful dynamic, it’s crucial to consider the experiences of estranged parents as well, acknowledging their grief, struggles, and the silent losses they endure.

Parental estrangement cuts deep, challenging fundamental aspects of identity and self-worth. Parents often wrestle with feelings of guilt, shame, and failure, questioning their role and effectiveness as a parent. Whilst estranged children may grapple with similar emotions, they often have opportunities to reflect, learn, and build meaningful relationships with their own families. For ageing parents, however, the window for reconciliation narrows leaving little chance for a “second go” at family.

Readers estranged from their parents may read this and feel strong emotions about the reality that the parent’s child is still there. It is important to acknowledge that reconciliation is not always possible. Relationships break down for complex reasons: traumatic events, irreconcilable personality differences, emotional disengagement, or a parent’s inability to address the issues that led to the estrangement.

Family estrangement - the physical distancing and emotional disconnect between family members - often stems from unresolved conflicts, betrayal, or deeply rooted disagreements. Unlike a physical loss through death, estrangement embodies an "ambiguous loss," a term coined by Pauline Boss. This form of loss is marked by the absence of closure—the person is physically gone but psychologically present, leaving the grieving process in a perpetual limbo.

As parents approach the end of their life, the ambiguity intensifies. They may experience anxiety about their will, healthcare decisions and funeral plans. Estrangement can complicate sibling dynamics, with those still in contact bearing the emotional and logistical burdens of caregiving. Financial matters may necessitate reaching out to the estranged child, placing additional strain on siblings caught between fractured relationships. These situations amplify the psychological presence of the absent child, deepening the parent’s sense of loss.

Ambiguous loss complicates grieving because it lacks societal rituals and recognition. Parents mourning estranged children do not receive the communal support typically afforded to bereaved individuals. The societal expectation that parent-child bonds are unbreakable exacerbates this pain, often silencing estranged parents and disenfranchising their grief.

Kenneth Doka’s concept of "disenfranchised grief" illuminates this hidden sorrow - grief that is not openly acknowledged or socially supported. This type of grief isolates parents, compounding their emotional distress and making it difficult to find solace or understanding.

Estrangement disrupts the life narrative, especially in later years when reflection and reconciliation hold psychologically significance. The absence of an adult child during critical life events - illnesses, milestones, or the death of a spouse – creates emotional voids that are difficult to reconcile. Parents may cling to the hope of reconciliation, only to face the painful reality that their efforts failed. This realisation can be both heartbreaking and humiliating, particularly as the estrangement becomes more visible to others as people possibly begin to question the absence of the adult child during crucial moments.

Estrangement rarely exists in isolation. Its effects ripple through extended family systems, straining relationships with grandchildren, siblings, and other relatives. An elderly parent may find themselves mourning the loss of being an active grandparent. They may need to come to terms with not gathering all their children together when needed. As they age, the absence of family support becomes more pronounced, leaving them vulnerable during medical emergencies or life transitions. This multifaceted loss can lead to chronic sadness, anxiety, and even physical health decline.

Understanding the complexities of parental estrangement requires compassion, both for oneself and others. Whether you are an estranged parent or child, acknowledging the depth of this loss can be the first step toward healing. For some, reconciliation may be possible; for others, acceptance and finding peace within oneself may be the goal.

By shedding light on the silent grief of estrangement, we can build a more compassionate dialogue around family relationships, loss, and the diverse ways people navigate the intricate ties that bind—or break—families apart.

Subscription benefit

This spring you can receive 20% off an annual subscription. Furthermore, founding members can access an additional benefit. All founding members can email me directly about their estrangement (or any family trouble) and will receive up to four personalised responses.

Other ways to support my writing

I have curated a list of books you might find useful or interesting. I receive 10% of your purchase and 10% goes to affiliated independent bookstores. A way to help me and not make Jeff Bezos richer!

I love reading your thoughts and they help to shape future posts.

My search for answers about my family’s dysfunction lead me finally to inter-generational traumatic narcissism. Daniel Shaw wrote two great books about it. I recommend them highly.

Once I learned about it. I felt my decision to cut my family off was a better decision than I had initially considered it. I originally thought it was a crude method of self-protection. I wasn’t feeling guilty about cutting them off, but Shaw’s books gave me greater appreciation that my decision was on solid ground. Disconnecting was likely the only solution since my parents were never going to change.

We have a right to protect ourselves from harm no matter the source. Parents and grandparents aren’t supposed to be harming their kids but there is a whole subset of parents/grandparents that do harm their kids/grandkids. Society needs to teach kids about harmful parents.

Reconciliation is ideal. But it’s not always realistic. Authoritarian parenting has created a society of children who were not given autonomy over themselves. Parents have caused great harm and abuse and refuse to take responsibility or even have a conversation about it. Now that these children are adults and understand the harm and abuse done to them, they have a right to be estranged. The kids are doing the hard work of breaking generational cycles of trauma.